The “Donativos”: Finding the Silver that Dropped through the Floor

Few people are aware of how important Spain’s material and military aid were to the colonist fight for independence against their British rulers. Without that aid the United States might not exist today. For many years, the colonies had carried the weight of the heavy price in taxes from the British government. The British government was in tremendous debt from colonial expansion and many years of war. Out of this initial colonial rebellion came the phrase “Taxation without Representation.” Other events such as the Boston Tea Party, that tinted the bay with broken tea barrels, led the way to revolution. These events sparked on July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence.

At the time of the colonist revolt, Spain ruled much of the territory west of the Mississippi River, as well as colonies in present day Hispanic America. As Spain had concerns that their other colonies might follow the path to independence, the Spanish government waited to officially declare war against the British until June of 1779. Additionally, Spain had her own desires to regain the islands of Minorca and Gibraltar from the British, having lost them for allying with France in the Seven Years War, our French and Indian War. Much of the initial material aid to the colonies provided by Spain, departed from the port of Bilbao through the company owned by Gardoqui e Hijos (Gardoqui & Sons), and was delivered through routes from Mexico and Cuba. The initial aid was sent in the name of France, as Spain had not officially declared war. This is one of the reasons, Spain has never really gained the proper recognition it deserves for this tremendous support.

Carlos Marichal, a well-known Mexican economic historian, states that “To finance the war against Great Britain, Viceroy of New Spain Martín de Mayorga managed to collect a grand total of over five million pesos”1, much of this was collected from Donativos.” Part of these sums, as we have indicated, were used to provide funds for the support to the French forces engaged in the war against the British. The French fleet was waiting in Barbados and the Windward Islands under obligations in the West Indies. The Spanish funds raised were crucial in providing provisions and salaries for French squadrons in anticipation of Comte de Grasse’s expedition into Chesapeake Bay. So, as you can see, there is much we owe the Spanish for their support to American Independence. Without their aid, Comte de Grasse would not have gotten to Yorktown when he did and perhaps we had never reached the victory.

Another, much larger portion of Spain’s financial assistance, was used to finance the successful campaigns of General Bernardo de Gálvez to retake Florida from the British and to consolidate Spanish control over the southern and middle Mississippi region. The Spanish government kept meticulous financial records and many of these are found in the National Archive of Mexico.

Two Spanish Task Force members, from the Daughters of the American Revolution, have searched in many archives for proof of these monies. Molly Long Fernández de Mesa and her sister, Mary Anthony Long Startz are on a mission to find one of the most forgotten monetary contributions to the war effort, called the Donativos. Here they open the window for you into their investigations.

The National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution or NSDAR, is the largest women’s volunteer organization in the United States founded in 1890 to promote education, historic preservation, and patriotism. NSDAR is a lineage-based society whose members descend from men and women who aided the cause of the American Revolution. In addition to the colonist themselves, many other countries aided the cause, including Spain. More than 1,025,000 women have joined the organization since it was founded over 125 years ago. Members are from the fifty United States, as well as eleven other countries, including Spain. One of the primary objectives is to honor the memory and spirit of the men and women who achieved American Independence. A Spanish Task Force was formed in 1998 with objectives that include: to open new avenues for membership for women who descend from Spanish Patriots, to locate documentation relating to Spanish contributions to the American Revolution, to identify Spanish nationals who contributed to the Revolutionary cause, to assemble lists of Spanish patriots, to locate records in archives outside of the United States, especially in Spain, Mexico, and Cuba. To this date some 500 Spanish Patriots have been proven, many who fought alongside Bernardo de Gálvez on the Gulf Coast and upper Mississippi River and Spanish Cattle Ranchers from Texas who supplied cattle for the Gálvez´s troops.

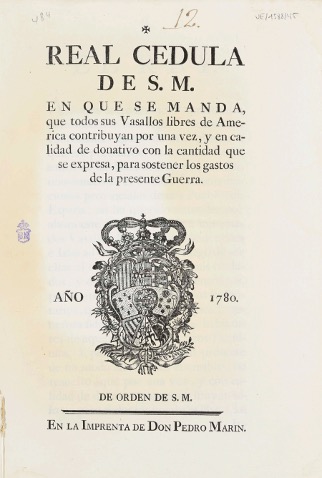

In October 2001, a list of Donativos contributed by soldiers of the Santa Fe Presidio, in present day New Mexico, dating from 1782 was found. Thus, sparking our flame to search for more. The Donativos are the result of Royal Decrees issued by the monarchs of a country, in this case Spain, to raise monies for the war effort. Different from a regular tax, they only typically occurred when there were specific military campaigns to finance. People who descend from Spanish subjects in Nuevo Espana who contributed to the war effort by giving a Donativo are considered to have given material aid. Thus, they are eligible to join NSDAR or in fact, Sons of the American Revolution www.SAR.org.

Above is the title page of the royal decree issued on August 17, 1780, by Carlos III, then King of Spain. The three-page document summarizes the King’s request of his subjects to come forth with a one-time donation to the war effort from the “continuous insults from the British.”

When the list of Donativos from the Presidio of Sante Fe and the Presidio of San Carlos de Cerrogordo in Parral, Chihuahua was discovered, we realized there had to be more lists hiding around in other archives, libraries, or private collections. Thus, armed with a volume reference from the DAR genealogy department, the sisters began to search the Archivo de Nacion in Mexico City. Molly and Anthony copied more than six-hundred pages of volume 17 of the Donativo lists in June of 2014. The National Archive in Mexico City is a castle like palace that was converted to a jail before it became the archive. It contains a large central patio with many extended wings that are easily accessible after completing the entrance requirements. “It was fascinating to hold these centuries old documents in white gloved covered hands while wearing masks. The feeling is indescribable when you can read the old Castilian Spanish and see the names. We are bringing these peoples contribution to light!” declared Molly. The list read very much like a census. They list the town, the names of the inhabitants and the amount of their contribution, followed by a total and name of the person locally responsible for collection. Not having time to copy the three additional volumes ten, fourteen and twenty-one that also cover the years for the American Revolution, the DAR later paid to have them copied.

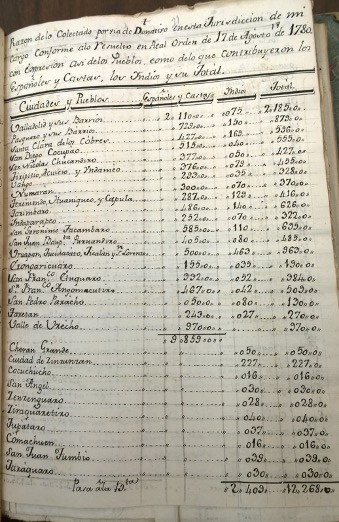

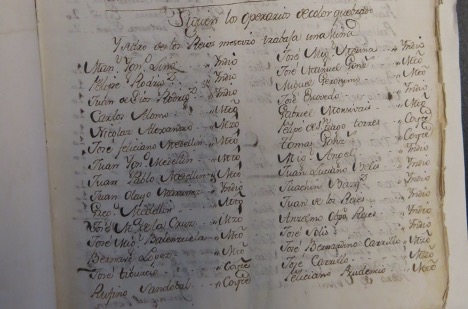

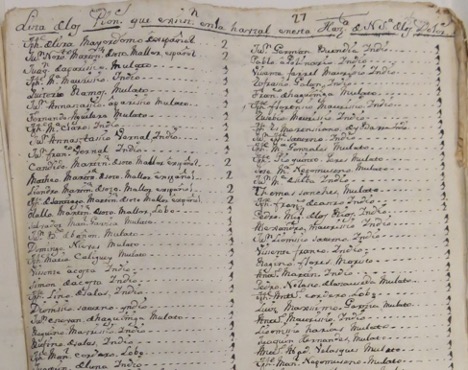

Seen on the lists are the names of the cities, towns, Spaniards, Castes and Indians and the amounts donated. Each Spanish citizen paid two pesos and each “Indio” or “Mestizo” paid one peso. Many ranch and factory owners paid for their servants, and we have read that some areas could not pay due to pandemics such as smallpox or famine.

Some of the localities in volume 17 include the present-day states of Guadalajara, Veracruz, Yucatan, Puebla, and Oaxaca. Included are several pages from areas near Mexico City. The largest cities today include the municipality and towns of Otumba and Axapusco. Many of the area names are still in existence including Barrio de San Marcos, Rancho de las Papas, Hacienda de Sr. Miguel Heuyapán, Hacienda de Tetepantla, Ranchos de Zacatepec and Puebla de San Miguel and Xaltepec in Puebla. In the four volumes found in Mexico City, the central to southern portions of Mexico are covered, all the way to the Yucatan. What has not been found yet, are the Donativos for the central part of Mexico through northern Mexico and the present day southern United States. The sisters have also searched in Colombia and Puerto Rico for additional lists.

This map of Nueva España from 1794 gives you a clear picture of how large an area the Spanish controlled and where we are searching for Donativo lists. The areas shown as green, Mexico and Nueva Galicia as well as the yellow Yucatan are where we have found lists. We are investigating to find the lists from the purple, orange and pink areas.

Volume seventeen from the AGN in Mexico City is now searchable on the Daughters of the American Revolution’s website. Volunteers are in the process of indexing the three additional volumes. They can be found under the genealogy tab section known as the GRS or Genealogical Research System. To view these records, go to DAR Genealogical Research Databases

This project and the commitment of the DAR volunteers indexing these names is an exciting opportunity for people of Hispanic descent to discover their previously hidden connection to a tremendous part of the history of the United States. Now the word must be spread, not only of these new records, but of the bigger story that so many people are unaware of.

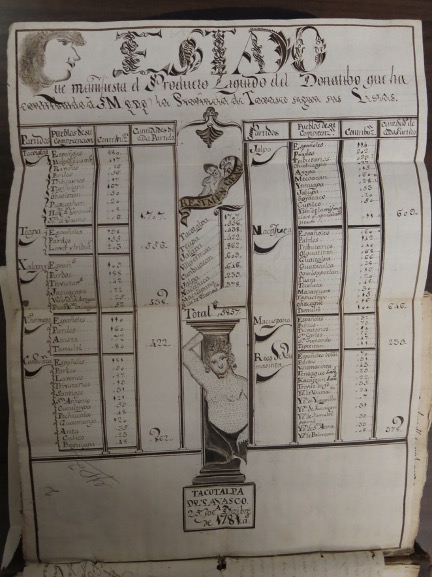

While highly historical, the dedication, creativity and efforts of the government officials who recorded these lists must be recognized. Next, we have selected samples from some of the lists to show you how they were recorded and reported to the officials. Many are considered a form of art expressed in the calligraphy. You can imagine the writer’s personality, education, and artistic talents. Often signatures have extra curves, loops, even scribbles defining their names. The first image is probably the most elaborate found from the many we have copied. Found in Volume 10 page 93, it is a totals page listing the towns of the province of Tabasco. The title has flowered script that evokes the passion flowing from the ink as he draws a woman figure on the top left corner overlooking the text. He continues with another, naked, supporting a column. His crowning flourish is an angel holding a banner with the words, resumen general. It has an architectural quality that illuminates the magic in the list.

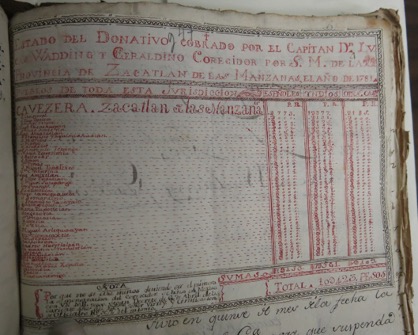

In the next image we have the extraordinary use of red color ink on this list identifying Captain Lucas Wadding Geraldino in the province of Zacatlan of the Manzanas, still famous today for its apple farms. Research tells us that the red ink was known as cactus blood. The red color is from a bug called, cochineal, that lives inside the cactus. It was a very important product alongside many spices being exported to Europe. Most red uniforms and clothing of this time was colored with this dye. The red ink helps the town names sweep across the left-hand column followed by dots that flow to the final count. You can see the special pride that was taken in the elaborate geometrically decorated borders and script.

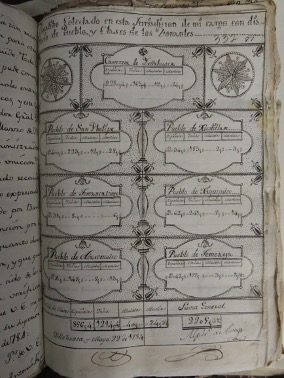

This next example is especially detailed similar to a family tree. Flower designs are present in the calligraphy with such precision that it just jumps off the page. The top corners have symmetrical circles filled with plant like star designs. Every corner is outlined with tulip flowers, some sustained by columns that could almost be vase-like. A perfect design in every way.

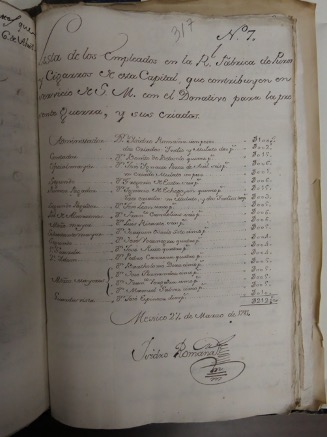

Next, we have, from Volume 10 dated May 27th,1781, a meticulous list of employees from a tobacco factory in Mexico City. A wonderful example verifying those asked, who made a donation had their names recorded. Often lists cover a wide variety of occupations from the local government and judicial officials. Military, ranches, churches, guilds including miners, silver makers, gun powder producers and card factories are examples we found. This example is signed by the administrator, Isidro Romana, with his original signature at the bottom with flowing lines.

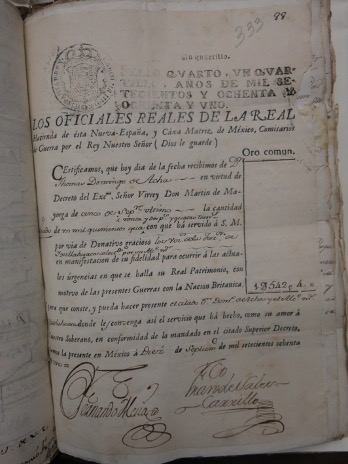

This page is an official government receipt of the Donativos being paid.

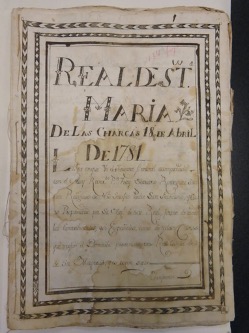

Recently a list of Donativos was located in the San Luis de Potosi city archive. This was very exciting to us. It is only about twenty pages; however, it separates the contributors on the list by Castes very clearly. Bringing their religion and culture with them, the Spanish married with the local peoples. Most Mexican people today are a highly variable mixture of European and Indigenous ancestry as well as possible African and Asian. Here you can see the cover page of Donativos from Charcas an important mining town in San Luis de Potosi and two other examples of the lists. It lists the monies collected by Lieutenant General José Ignacio de Herrera and Fray Mariano Rodriquez Saenz.

Lista de los contribuyentes, así españoles como de todas las castas que exigen el donativo prevenido por Real Cédula de Su Majestad, formada por el Teniente General José Ignacio de Herrera, acompañado del muy Reverendo Padre Fray Mariano Rodríguez Sáenz, religioso de la orden de San Francisco y cura propietario del Real de Santa María de las Charcas. exp. 6, 70 fs. Contiene un impreso. Portada con margen resaltado.

Folio 17. Archive San Luis Potosí

The San Luis Potosí Donativo list found by the sisters shows Castes separated by such categories as Españoles, Indios, Mulatos, Lobos and Coyotes. This brings to light just how many peoples participated in the collection. This list you can read clearly the names and the Castes; Indio, Mestizo and Coyote.

In this list you can also clearly read the family names plus the description of the different Castes; Español, Indio, Mulato and Lobo.

According toAna Gonzalez-Barrera, a senior researcher focusing on Hispanics, immigration, and demographics at the Pew Research Center, “The term _mestizo_means mixed in Spanish and is generally used throughout Latin America to describe people of mixed ancestry with a white European and an indigenous background. Similarly, the term “Mulatto” –_Mulato_in Spanish – commonly refers to a mixed-race ancestry that includes white European and black African roots.”

The poster explains with pictures the family group for the different Castes.

In 2006, the President General of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Presley Merritt Wagoner, dedicated a historical marker in Madrid, Spain in the gardens of the Casa de America. The plaque reads,

Commemorating Spanish Aid to the Independence of the United States of America

This plaque commemorates Spanish aid to the United States of America, 1776-1783. His Majesty King Carlos III provided diplomatic support through the Count of Floridablanca and the Count of Aranda and military and naval expeditions under Bernardo de Gálvez in the Gulf of Mexico. Spain also contributed financial aid for supplies, including cannons, gunpowder, tents, uniforms, quinine, and food distributed via Havana and Mexico. The Treaty of Friendship, Limits and Navigation was signed at Real Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial, on October 27, 1795, formalizing a supportive and enduring diplomatic relationship. Spain's important role during the American War for Independence is acknowledged with gratitude.

As we live in a global society with multicultural identities, this is the perfect way to share the story of Spain’s forgotten role in the war for American Independence. What better way to open doors of friendship than to do more genealogical, cultural, historical, and archeological studies of our rich Spanish heritage. What an opportunity to honor those with Hispanic heritage than to find their ancestors on these lists! We are privileged to be adding to this webpage Unveiling Memories and are grateful for the fantastic work being done by Iberdrola and their American subsidiary Avangrid. Their work began with La Memoria Recobrada. Huellas en la Historia de los Estados Unidos which opened in Bilbao, May 2017. It continued on with the exhibition Recovered Memories Spain and the Support for the American Revolution in New Orleans and Washington D.C. in 2018. The sisters join hands in unveiling these Donativos. The search continues!